An Anglican friend of mine recently commented that he was looking forward to the year 2054. Puzzled, I asked, “Why 2054?” He explained that 2054 would mark one thousand years since 1054 when the Great Schism took place. He went on to explain that he and others were hoping that by 2054 Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Orthodox Christians would all be reunited. I responded by saying that while the Great Schism of 1054 was a great tragedy and that the reunion of Christians would be laudable, there remain significant differences between Anglicanism and Orthodoxy. This article is an expansion on that brief remark.

The Filioque Phrase

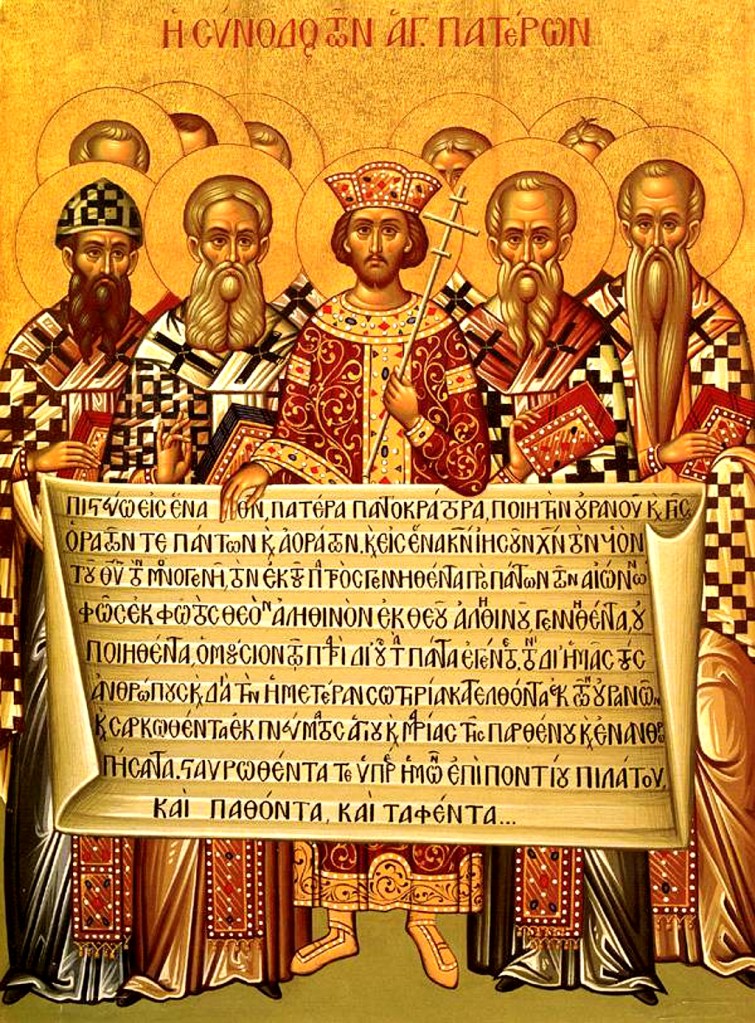

The Nicene Creed was meant to be the universal creed for all Christians, yet Anglicans, Roman Catholics, and mainline Protestants use an altered version of the Nicene Creed. When they recite the Nicene Creed, they insert “and the Son” into the passage about the Holy Spirit.

The “Filioque” is a Latin phrase meaning “and the Son.” It was first added to the Nicene Creed at the Third Council of Toledo (589) at the direction of King Reccared. The interpolation was made to signify Spain’s rejection of Arianism and its embrace of the Catholic Faith. Many, however, found the Filioque objectionable. Even a pope objected—Leo III went so far as to have two silver shields made to display the unaltered Nicene Creed in Greek and Latin. The Filioque remained confined to the West and was never part of the patristic consensus. The situation changed when a pope added the Filioque to the Nicene Creed. In 1014, Pope Benedict VIII inserted the Filioque on the occasion of the coronation of Henry II as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. With this, the Filioque became normative for Roman Catholics and was elevated to the status of dogma. This was done despite the absence of an Ecumenical Council. This unilateral action by a pope would lead to the Great Schism of 1054.

The popularity of the Filioque among Western Christians is due in large part to their theology being based upon Augustine of Hippo. Augustine’s understanding of the Trinity included his notion of the double procession of the Holy Spirit. Orthodoxy find this teaching theologically suspect due to the implicit demotion of the Holy Spirit within the Trinity. Theologically, Anglicanism has more in common with Roman Catholicism than with the undivided Church of the first millennium and the patristic consensus. Beyond dropping the Filioque, it would also help if Anglicans, especially their clergy, were to become familiar with the teachings of the Cappadocian Fathers: Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus, on the Trinity.

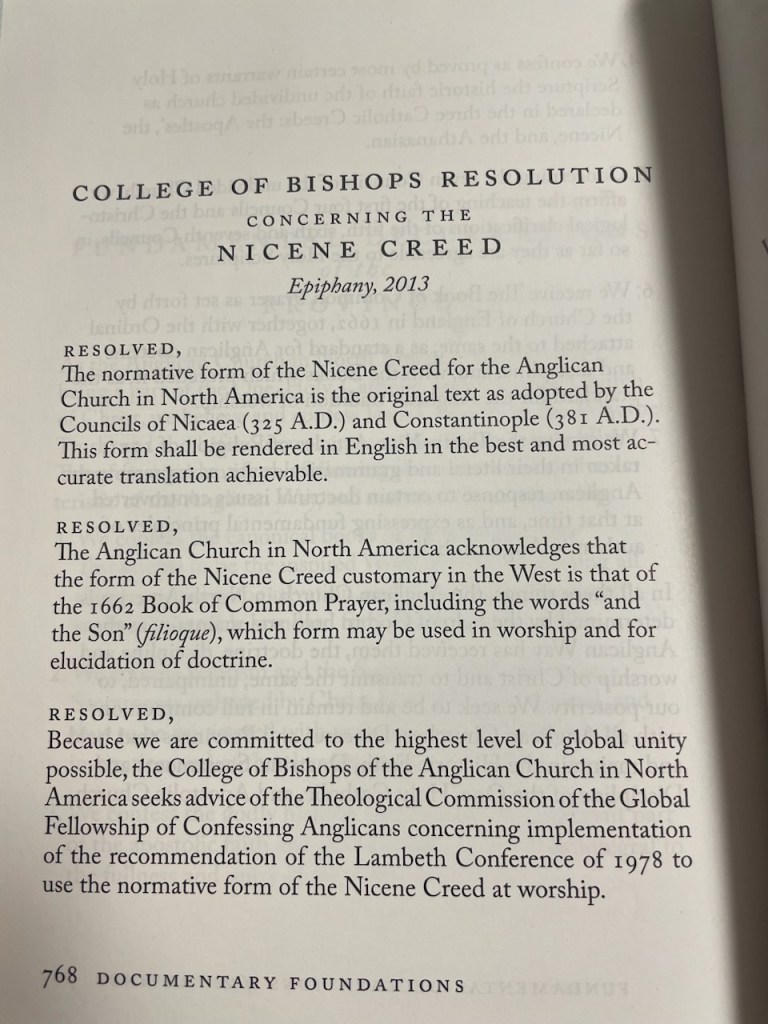

From time to time, I’ll visit my Anglican friends’ church. Upon entering, I’ll be given a printed order of service. After sitting down, I usually look over the songs and sermon title. Then I’ll turn to the Nicene Creed and see if they have dropped the Filioque phrase. From what I have seen so far, nothing has changed. My Anglican friends who are attracted to Orthodoxy tell me that they agree that the Filioque should not have been inserted into the Nicene Creed and that they prefer the more traditional version used by the Orthodox Church. Recently, one of them sent me a camera shot of the 2013 College of Bishops’ Resolution that affirmed the Nicene Creed of 325 and the Constantinopolitan Creed of 381 are to be considered normative for ACNA (Anglican Churches of North America).

However, that document went to note that the western form of the Nicene Creed, which contains the Filioque “may be used in worship and for elucidation of doctrine.” The resolution concludes with a request for advice on how to implement the resolution. But so far, no substantive change has taken place.

The efforts made by Anglicans to unite with Orthodoxy strikes me as timid and half-hearted. In this article, I offer some perspectives and advice about the prospects for union between Anglicans and Orthodoxy. I want to take a receptive and optimistic approach rather than a harsh, judgmental approach. However, this optimism must be tempered with realism and pragmatism.

Three Premises of Orthodoxy

Any discussion of union between Anglicanism and Orthodoxy must start with a proper understanding of Orthodoxy’s adherence to Tradition with a capital “T.” What defines Orthodoxy is the safeguarding of Tradition without change. Orthodoxy rejects the Filioque because it was unilaterally inserted by the Bishop of Rome without the endorsement of an Ecumenical Council. For this reason, Orthodoxy considers the Filioque to be an unwarranted innovation. Another essential point is that Orthodox theology is expressed primarily in its Liturgy, not in theological texts or in synodal resolutions. One further point is that the Seven Ecumenical Councils constitute the normative theological framework for Orthodoxy. Any successful union between Orthodoxy and Anglicanism will require that Anglicans accept all Seven Ecumenical Councils, even Nicea II (787) which calls for the veneration of icons.

I enjoy being with my Anglican friends because we have much in common. Like me, many of my Anglican friends are Evangelicals drawn to the Ancient Faith and the ancient liturgies. When I visit their church services, rather than scrutinize what their pastor has to say in his sermon, I pay close attention to their order of worship. My three suggestions presented below are quite simple and can be implemented the following Sunday.

1. Drop the Filioque Phrase

I look forward to the day when I visit my Anglican friends’ church and upon examining the Nicene Creed, I find it to be identical to that used in my Orthodox parish. While it would help if the pastor were to state he has problems with the Filioque, the essential thing is that the printed order of worship leaves out altogether the Filioque. Linguistic devices such as asterisks and parentheses are to be avoided as these would be unacceptable to Orthodoxy. If Anglicans find this recommendation too difficult to accept, I will not be offended. I will recognize that they and their faith tradition have decided to walk apart from the Orthodox Church.

2. Include the Hymn “More Honorable Than the Cherubim”

While Anglicans and many mainline Protestants claim to accept the first four Ecumenical Councils: Nicea I, Constantinople I, Ephesus, and Chalcedon, they are de facto Nestorian. (Nestorianism is the heresy that refuses to acknowledge that the Virgin Mary gave birth to the God-Man Jesus. This is implied by the refusal to address Mary as the “Mother of God.” By only affirming that Mary gave birth to a human Jesus, Nestorians split Jesus’ humanity from his divinity resulting in a heretical Christology.) Rather than pass a resolution affirming the statements made at the Third and Fourth Ecumenical Councils that the Virgin Mary is the Theotokos: God-Bearer or Mother of God, it is far more important that the Virgin Mary be acknowledged as the Theotokos in the order of worship. On a few occasions, I told my Anglican deacon friend who has the responsibility of putting together the worship bulletin: “All you have to do is insert the hymn “More honorable than the cherubim” into your worship bulletin. It’s that simple!” That last sentence is said tongue in cheek because I know that for him it is far from a simple matter.

It is truly meet to bless thee, O Theotokos,

ever blessed and most blameless and the Mother of our God:

More honourable than the Cherubim,

and more glorious beyond compare than the Seraphim,

who without corruption gave birth to God the Word,

true Theotokos, we magnify thee.

YouTube video: “Magnificat (Megalynarion) to the Theotokos” [3:38]

This hymn—known as the Megalynarion—is sung at every Orthodox Liturgy. It is sung immediately after the consecration of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist. Every Orthodox Christian knows this hymn. It is not a nice add-on but rather an affirmation of a core doctrine: the Incarnation of God the Son for our salvation. This is an issue that rarely come up in our discussion, but it is an issue that must be faced if Anglicans truly desire unity with Orthodoxy.

3. Bring Icons into the Church

I have been pleasantly surprised to learn that many of my Anglican friends affirm that the Eucharist is to be the focal point of Sunday worship and that they believe in the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist. (Whether Anglicans have a valid Eucharist and episcopacy are issues I reserve for another occasion.) However, I am struck by the absence of icons when I visit their church services. I see an altar for the celebration of the Eucharist; I see vested clergy; I see strong similarities between their order of worship and the Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom used at the local Orthodox parish I attend; but I am struck by the absence of icons. Icons are the hallmark of any Orthodox church. No matter where you go, you will find icons of Christ and the Virgin Mary in an Orthodox church. This is because the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea II, 787) decreed that icons are a normative part of Christianity. Icons have been described as windows to heaven. They possess a sacramental quality that links the visible material world we inhabit with the invisible Kingdom of God. The presence of icons in a church would signify the hearty acceptance of the Seventh Ecumenical Council.

St. Stephen Orthodox Mission – Stephenville, TN (Source)

If my Anglican friends seriously desire union with Orthodoxy, my suggestion is that they order two 8.5” by 11” icons: the Pantocrator icon of Christ and the icon of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child; and that they place the two icons in front between the altar and the congregation. One key element would be the clergy and the members of the congregation venerating the icons. Usually when Orthodox Christians venerate an icon, they will bow down and kiss it. This may be too much for many Anglicans. My suggestion is that as the clergy process into the church, they bow at the waist to the icons to show reverence. Another suggestion is that members of the congregation bow or genuflect to the icons as they come forward to receive Holy Communion. The important thing to keep in mind is that one is not reverencing the picture but rather the person depicted in the picture.

Implementing these suggestions is not all that expensive, but it would be quite a challenge on grounds of theology and conscience. I recognize the serious difficulties contained in this suggestion for my Anglican friends, but I want to make clear to them that if they are truly desirous of union with Orthodoxy that the acceptance of icons and the veneration of icons are essential, non-negotiable items. Icons are an integral part of Christian worship. Churches without icons and worship services without the veneration of Jesus Christ and the saints constitute a break from historic Christianity. If my Anglican friends were to accept icons and venerate icons in their Sunday worship, they will have taken a giant step towards union with Orthodoxy and with the Ancient Church.

Anglicans’ Distance from the Seven Ecumenical Councils

Any fruitful engagement between Anglicans and Orthodoxy must be grounded in the Seven Ecumenical Councils. It may come as a shock but my Anglican friends must face the fact that their faith tradition has diverged significantly from the Seven Ecumenical Councils.

Anglicans depart from the First and Second Ecumenical Councils (Nicea I, 325 and Constantinople I, 381) when they recite the “Nicene Creed” which dates back to 1014.

In their Sunday worship, my Anglican friends implicitly reject the Third Ecumenical Council (Ephesus 431) and the Fourth Ecumenical Council (Chalcedon 451) when they omit the hymn “More Honorable than the Cherubim” which explicitly calls Mary the Theotokos (Mother of God).

Many Anglicans, especially those of low church or of Reformed persuasion, are unabashedly iconoclasts. They unequivocally reject the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea II 787). This is where Anglicanism most sharply diverges from Orthodoxy.

Here we see Anglicans rejecting 5 out of 7 Ecumenical Councils. Thus, the gap between conservative Anglicans and Orthodoxy is wider than most suspect.

Closing the gap can be done, but it won’t be easy. If conservative Anglicans—those affiliated with ACNA and GAFCON—were to implement these three steps collectively, then rapprochement between the two traditions can be considered a real possibility.

Closing Questions

Let me frank and say this: Orthodoxy is a hard road to travel. Nonetheless, it is worth the cost because Orthodoxy is the true Faith. We are not going to change or compromise on Tradition. If you want to reunite with the Ancient Church, with the Church Fathers, and with the Ecumenical Councils, we will help you. If you are not ready, we will wait. If you decide to continue to walk a different path, we will recognize your freedom to choose such.

Anglicanism has from its inception had something of an identity crisis: It does not know whether it is Catholic or Protestant. From time to time, I’ll ask my Anglican friends: “What are you? Are you Catholic? Or are you Protestant?” In the meantime, my recommendation for my Anglican friends is that they continue to study the early Church Fathers, the Seven Ecumenical Councils, the lives of the saints, and church history. Study the history of Anglicanism and compare it against the early Church prior to the 1054 Great Schism. The quest for unity with Orthodoxy should be motivated by a desire for unity with the undivided Church of the first millennium.

I close with two questions:

Question 1 – Are there signs that Anglican churches in ACNA or GAFCON are taking the three steps I presented?

Question 2 – If there are few signs of ACNA or GAFCON embracing the ancient forms of worship, why wait until 2054? Why not visit the local Orthodox parish in your area and investigate becoming a catechumen?

On the issue of Anglicanism dropping the filioque: several decades ago, the Anglican Consultative Council recommended that they do just that. In response, the Scottish Episcopal Church for one has not used the filioque in its liturgies since about 1980.

Regarding the megalynarion, while it is not a formal part of Anglican liturgies, most Anglo-Catholics would have no difficulty with its use (and I know some who use it informally).

And icons are often found in Anglican churches (at least, in the United Kingdom). Unfortunately, they tend to be seen as items of decoration rather than objects of veneration.

The problem with Anglicanism is not its resistance to Orthodox doctrines and practices but its assumption that these are merely optional – just one way of being Christian. It is perfectly possible to be ‘orthodox’ within Anglicanism, but it is also perfectly possible to be an Anglican priest and deny the reality of God (e.g. Don Cupitt) or suggest that Jesus was homosexual (e.g. Hugh Montefiore) or campaign for same-sex marriage or . . .

LikeLike

Lawrence Osborn – Thank you for engaging my article! I was not aware of the Scottish Episcopal Church dropping the Filioque, but I believe your other two points are accurate in their assessment of the current state of general Anglicanism. That is why I directed my article to my Anglican friends in ACNA and GAFCON. In my view, these two groups are the closest to Orthodoxy.

LikeLike